Hi all,

Sorry for my recent absence and lack of writing, I have been applying to PhD programs and having to write many an essay and statements of purpose wore ol’ gal out. This week I spent some time with friends and family as a respite from my applications. Last night I partook in delicious Korean food with my very good friends Kristen and MJP. Earlier in the week, my older sister Adwoa and I went to see a holiday special by the Edmonton Opera house which was cozy and exciting. Overall, I had a great and wholesome week.

This week I want to discuss one of my essay topics that I wrote for my PhD applications. I promise it won’t be soppy. For one of my personal essays I wrote about how as a racialized/black woman, I had in many insidious ways, internalized anti-blackness as a means to survive my childhood spent in predominantly white spaces that were not conducive to the self-esteem of little black girls with something to say. I wrote about how I have come to understand normalcy as being white, thin, and straight and proceeded to make myself fit the mold as much as possible, otherwise known as “getting close to normal as possible.” As an adult who has engaged in many a decolonial and anti-racist practices, I realize how harmful my thoughts and beliefs as a child were, but I also realize that I was an impressionable child and easily led into fuckerry.

This week I reflect on the story of Sara Baartman and the reverberations of her story in black feminist art. I discuss the lineage of white supremacist discourses that have long associated blackness with degeneracy and abnormality. This may be a heavy topic for some, but I promise it’s a good read and a necessary one, not because I wrote it but because the stories I am sharing here are pertinent in examining internalized prejudices and other such consequences of being alive and well aware.

Finally, I would like to welcome my new readers courtesy of Little’s and Tara Giancaspro’s recommendations. I cannot thank ya’ll enough for encouraging people to read my ramblings.

Sincerely,

your dearest sister killjoy

Reflections | 04

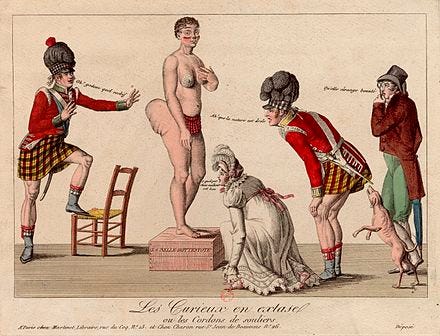

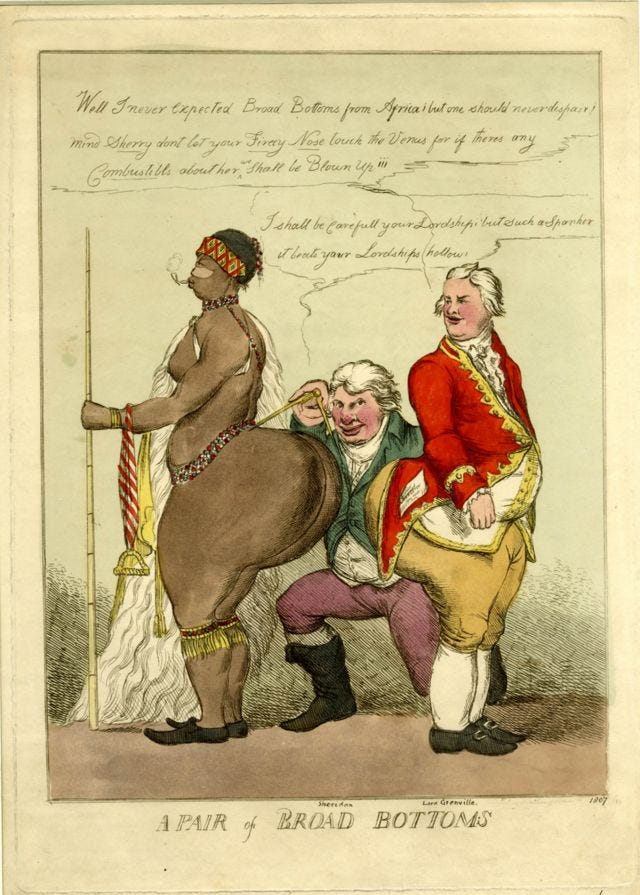

When I was an undergrad, I wrote my honours thesis on how colonial narratives about the black body and in particular the black female body marked blackness as inherently inferior to whiteness. While researching this thesis, I happened on the story of Sara Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus who was put on display in 19th century European freak shows as an example of black deviance and inherent inferiority. When she died, her body was acquired by French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier. Cuvier, a dedicated scientific racist, dissected Baartman’s body looking for empirical evidence that black people were innately inferior to white people and that Baartman as a black woman was the “missing link” between the human race (white people) and orangoutangs. After he was done, her body was stuffed and put on display at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris where she remained until 2002 when she was repatriated to South Africa for burial. Although she was on display until the 1980s the fact that Baartman’s body remained in museum storage until it was advocated for her to return home is in itself chilling.

Researching and reading about Baartman’s story, I was once again confronted with the white supremacist binary that black people were the innate antithesis to whiteness and as such were not “normal” and should not be treated as such. As an undergraduate, and to this day, I was/am interested in reclaiming the subjectivities of black and racialized folks from the monoliths created by white supremacy to mark blackness as deviant from the white norm. As such, I looked to art by racialized and black women artists to understand in what ways they were challenging colonial narratives that centred the black (female) body as the ultimate divergence from the perceived norm of whiteness. Many artists come to mind, but I want to discuss Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s 1992-1993 performance The Couple in the Cage: Two Amerindians Visit the West and Reneé Cox’s 1994 piece Hottentot Venus.

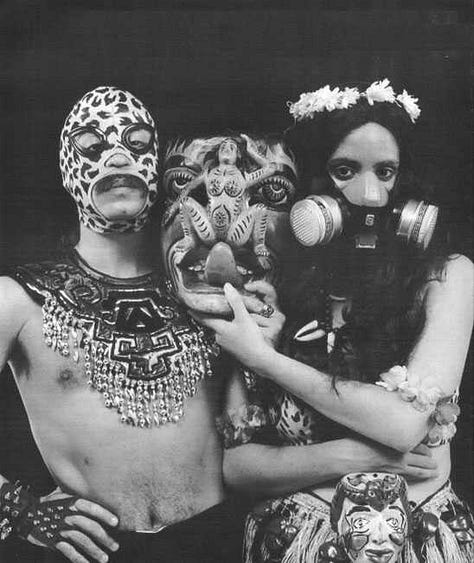

The Couple in the Cage: Two Amerindians Visit the West was performed during the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival to the Americas and coincided with celebrations of this event. In performing The Couple in the Cage, Fusco and Gómez-Peña were not only challenging the imperialistic myth that America was “discovered” by Columbus, but were also dissecting the myths put forth by the display of racialized people like Baartman and scientific racists like Cuvier. For this performance, Fusco and Gómez-Peña were confined to a golden cage that held items like a television, books, magazines and other cultural artifacts. On the cage were pseudo-scientific diagrams describing the histories and culture of the Guatinaui, a fictional island and culture located vaguely in south America. Fusco and Gómez-Peña were dressed in their “traditional Guatinaui dress” which for Fusco was grass-straw skirt and a bikini top and Gómez-Peña wore a wrestling mask and brand name sneakers. Fusco would perform “traditional Guatinaui dances” while Gómez-Peña would tell Guatinaui folktales in a made-up language. What was revealing about this performance was the reactions of people to Fusco and Gómez-Peña. Speaking to Anna Johnson from Bomb Magazine in 1993 Fusco recollects : “There were people who were not sure whether to believe that we were real. Other people were absolutely convinced that they understood Guillermo’s language, which is virtually impossible because it’s a nonsense language. One man in London stood there and translated Guillermo’s story for another visitor”. This arrogance of the visitor in wanting to translate and intercept Gómez-Peña’s made-up stories in a made-up language that nobody understood was/is astounding to me and goes to show how arrogant white supremacy can and will be against all odds.

Another reaction that was especially telling was the sexual aggression towards Fusco. That Fusco, a racialized woman was placed in a vulnerable position of the observed and experienced sexual aggression from mostly white males for me speaks to the experience that as a racialized woman Baartman may have experienced during her time on display in Europe. In fact, it is known that Baartman was seen as a sexual oddity because she was black and had a protruding bottom. Before Cuvier took possession of Baartman’s body when she died, she was examined by Cuvier and his colleague, another scientific racist, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Upon examining Baartman they deemed two aspects of her body not only as proof of her inferiority, but as proof of her hypersexuality and as such the lasciviousness of black folks. The first was the “Hottentot Apron,” a body modification practiced by the Khoisan Tribe (Baartman’s tribe) in which the labia minora is elongated as a sign of beauty. The second was her protruding bottom. Like the arrogant twerp that stood translating Gómez-Peña’s made-up language, Cuvier and Saint-Hilaire were loud and wrong, but unfortunately were in positions of power that granted authority over the narrative of Baartman and as such these features of Baartman’s body became associated anti-black with colonial discourses about black folks.

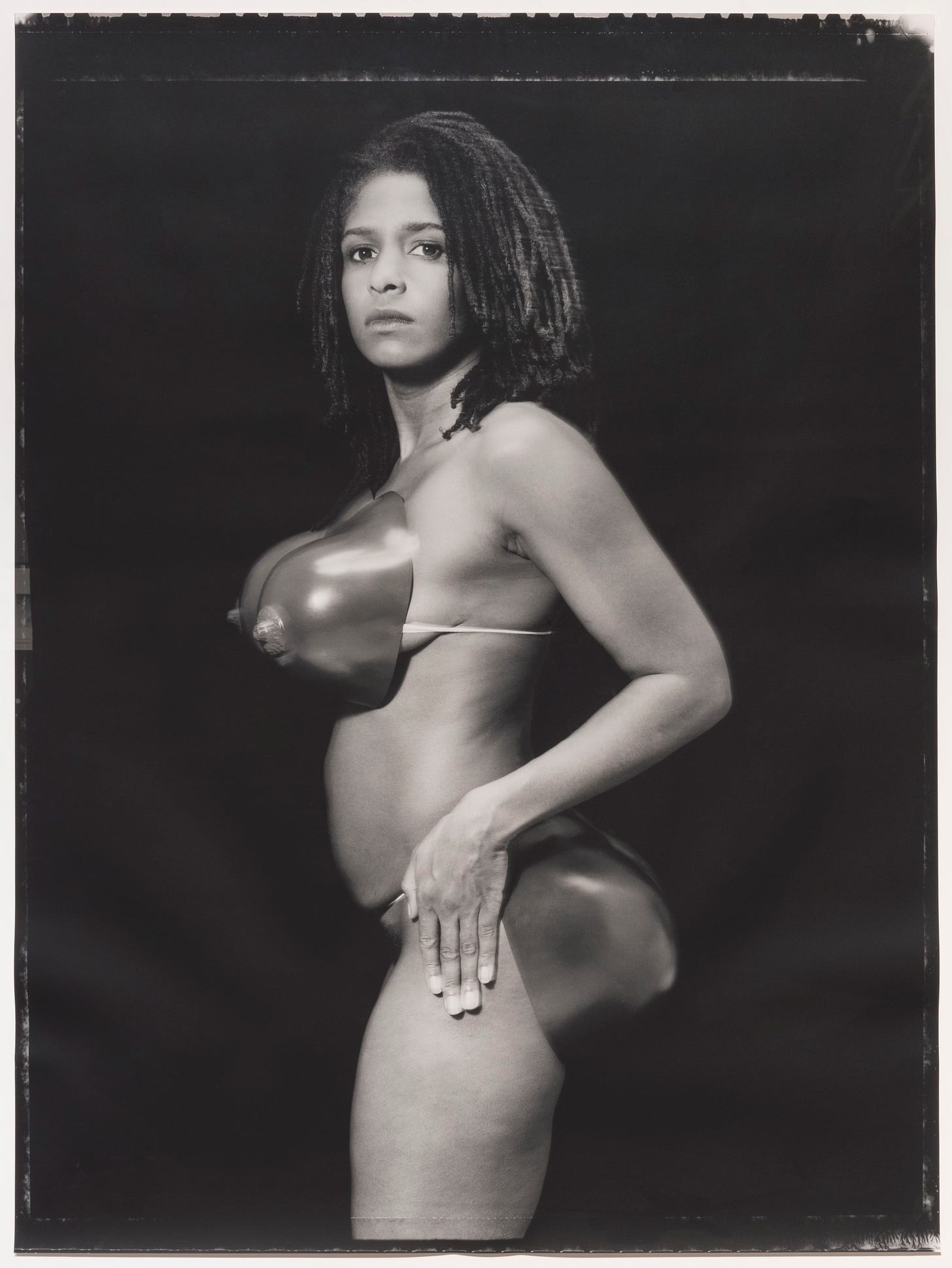

In 1994, Jamaican-American artist Reneé Cox would also reckon with the legacies of Baartman’s display. In a black and white photograph, Cox stands in side view pose, her head turned to face the viewer, her gaze directly intercepting the viewer’s gaze. She wears large plastic casts of breasts and a large plastic cast of protruding buttocks. In doing so, Cox directly challenges the viewer as well as the racist myths put forth by Baartman’s display. Unlike Baartman who was not complicit in the narratives told about her, Cox’s rendition of Baartman reclaims autonomy by first, highlighting that the attributes that were considered markers of Baartman’s inferiority were subject to the differing and innately white supremacist beauty standards of Cuvier and Saint-Hilaire. Secondly, by confronting the viewer with her gaze, Cox is also reclaiming power, she observes much in the same way that she is observed, muddling the dynamics of power that rendered Fusco and most definitely Baartman subject to sexual harassment.

In reflecting on Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s work as well as briefly looking at Cox’s work, I am reminded that as an individual whose body is a marker of difference much in the same way as the artists and Baartman, I am at times subject to the unpleasant fuckerry that comes along with it. In the times when I feel the despair of difference, I no longer look to move closer to the white supremacy framework of normalcy, instead, I sit with myself and let the madness linger until I have the strength to shift it into the dumpster fire it deserves. If you have read to the end, thank you and I hope you will take the time to reflect on these works as well.