Hi Y’all!

I hope you spent your week in good spirits. This has been the coziest week for me so far this year, lots of walkabouts and hanging out with friends. On Thursday, I spent the evening with my good friend Kristen at the art gallery and ended my night with my older sister Adwoa on a theatre date. We saw Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, which if you haven’t seen it, is a play about the ridiculousness and blunders of upper class England or more specifically the London crowd. On friday, I spent the day working (attending fancy events and writing). I love my new job! This week was the week of Anohni of Anohni and the Johnsons fame. Anohni’s most recent album My Back Was a Bridge For You To Cross was the sensational soundtrack to my week. Packed full of heart and brilliance, this album, which you can listen to here, captures the soul of Queer rebelliousness. The cover art of the album features a black and white portrait of Marsha P. Johnson looking positively regal. Marsha was a key activist along with Sylvia Rivera in securing gay and trangender rights along with making visible those marginalized by incessant homophobia and transphobia. Today, she remains the guardian angel of many.

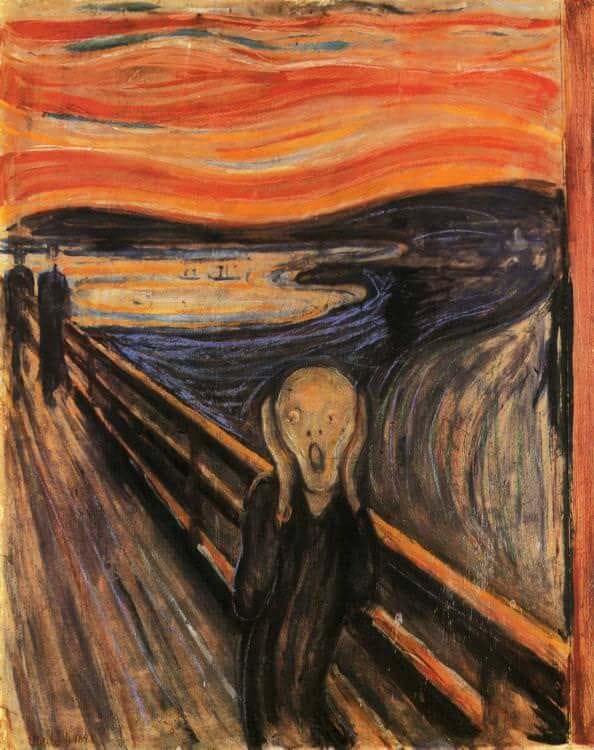

In Canada September 30 (today) is Orange Shirt Day, a day set aside to commemorate the Indigenous children who were victimized by the Canadian residential school system. Orange Shirt Day was created by Phyllis Webstad of Stswecem’c Xgat’tem who tells the powerful story of having her orange shirt taken away from her when she was forced into the residential school system. To celebrate and commemorate the children whose lives were shattered by the egregious system of residential schools, I choose to write about Kent Monkman’s The Scream, 2016. It is an understatement to call this painting powerful. It is especially important for me because in Edmonton, at Grandin station, the tearing away of Indigenous children from their communities is depicted with comfortable joy. However, Monkman’s The Scream showcases the heart wrenching helplessness of the situation.

As always,

Your Sister Killjoy

The Scream is a history painting that depicts the realities and reverberating effects of the residential school system. The residential school system was a ploy by the Canadian Government, beginning in the late nineteenth century, to aggressively assimilate Indigenous peoples by kidnapping their children and forcing them to reject their communities and heritage. Between the late 1800s and the 1990s More than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were forced to attend residential schools whose only objective was to strip them of their language, culture, and identity. Many children suffered physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, and several thousand died. Today, Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous children, continue to feel the effects of the residential school system through generational trauma.

In the painting, the instances of generational trauma are not only depicted in the agonizing faces of the mothers or the confused and distraught expressions of the children, but the modern clothing of the Indigenous individuals also showcase the continued impact of the residential school system on Indigenous communities. Additionally, the clothing worn by the perpetrators of kidnapping Indigenous children wear uniforms that can only be described as timeless, so the viewer cannot pinpoint the exact moment in time this painting is depicting. As such, while The Scream is a history painting, Monkman reminds his audience through the choice of clothing that history was not so long ago and that the impact of the residential school system and threat to Indigenous communities are ever present .

The imagery of this painting is especially chilling for me when I consider its namesake link to Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s 1893 painting The Scream. Painted across the globe at the same moment when Indigenous children were first being torn from their communities, it documents an “expressionistic construction” based on an experience that Munch had. According to the painter, he experienced a scream piercing through nature while on a walk. Pondering on both paintings as I write this, I consider the deep psychic possibility that the scream that pierced nature may have come from the parents/communities depicted in Monkman’s visceral painting. A collective cry as the Catholic Church and Canadian Government collaboratively tore away their children.

In 2017, The Scream was part of “Chapter V: Forcible Transfer of Children,” where it hung in a room with black walls. The entrance to the gallery space featured toys and crafts made by students at the Grouard Residential School circa 1925, and these objects carried the cultural identity of the children who incorporated hide and seed beads into their making. The walls were lined with askotâskopison (traditional cradle boards) crafted by mothers for their babies. Some were plain wood frames or chalk-marked outlines suggesting missing and deceased children. In the accompanying brochure written in Miss Chief Eagle Testickle’s voice, the pain is inexplicable: “This is the one I cannot talk about. The pain is too deep. We were never the same.”1

https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/kent-monkman/key-works/the-scream/#